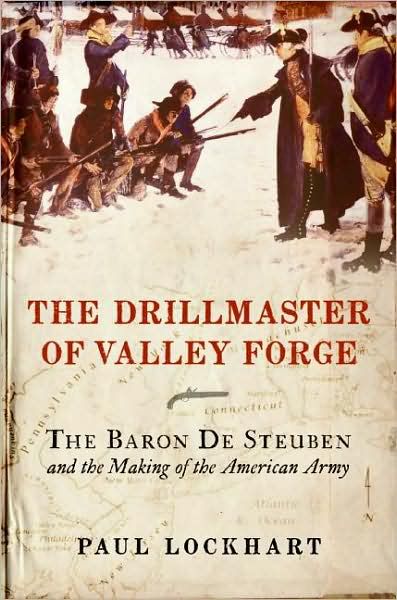

The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army

Paul Douglas Lockhart

Publisher: Collins (September 9, 2008)

Frederich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerard Agustin von Steuben was born on September 30th 1730, among the godfathers for whom he was named was King Frederich William I of Prussia, with his permission. His father was an engineer in the Prussian Army a holder of the Pour le Merit a soldier of great reputation and no wealth. Steuben joined the Prussian army at fourteen and followed the usual steps of a regimental officers career for ten years until the Seven Years War. He distinguished himself as a regimental officer, in an elite light infantry battalion, and then in a number of staff positions from brigade to the Army Staff. Near the end of the war Frederick the Great selected him for advanced training. But at the end of the war, despite being known as an up and coming officer he was discharged for reasons that are not entirely clear. He was employed as the Court Chamberlain of the minor German State of Hohenzollern-Hechingen until his efforts to find military employment let him the American side in the Revolution. While Chamberlain he was awarded the title the Frieheer, loosely equivalent to a British knighthood, but translated into French as Baron. Thus he was Baron de Steuben. But not “Baron von Steuben” which would represent a very different position.

Benjamin Franklin got him an appointment to the Continental Army. Washington appointed de Steuben as Inspector General with the rank of Major General. At that time this position was more similar to a G-3, operations, than the ombudsman and administrative inspector of the modern army. The biggest problem at the time was the Army had no consistent method of training drill or discipline. Each regiment followed the drill of the commanders drill book (there were several in publication) and this was done to varying levels of commitment and success. His solution was to form a model company to teach a basic drill then send it’s members back to their units to act as instructors. He established a through inspection program to see that it was done. He cut quite a figure, riding through camp with the pomp of a Prussian General and major nobility, on the drill field, personally demonstrating and correcting, swearing like a trooper, and always, when inspecting putting the welfare of the soldiers on the same basis as drill. In three months, even after the devastating winter of 1777/78 the Continentals were a disciplined and trained army with confidence in there own abilities.

That spring of 1778 the British retreated from Philadelphia to New York by land, Washington set off to intercept him, knowing he could not defeat the larger force he planned to cut off and defeat the rear of the British column. The lead of the attack was entrusted (by seniority and politics) to General Horatio Gates whose poor planning and execution caused the attack to stall then he ordered the army to retreat. However with there new found confidence and training individual regiments held together as disciplined units, they knew they hadn’t been defeated and wanted to fight. Washington came up, rallied the Army and turned the retreat into a defense and then counter attacked. Something the Continental Army could not have done a few months earlier. De Steuben commanded the reconnaissance forces for the Army and provided Washington with excellent intelligence on where the British were and what they were doing. He also played a key role in turning the retreat around.

After this he continued to serve as Inspector General, made a number of reforms, and served as a temporary field commander when Washington needed someone with special abilities. An outsider with no alliance to the many factions he could accomplish this where other officers would have had their efforts lost to politics. But this also denied him an assignment to a major command. He wrote the Army’s first Drill Manual which remained in effect until 1812, while the tactical parts are long outdated, the section on leadership is still good guidance.

In 1780 de Steuben was appointed second in command for Nathaniel Green’s campaign to recapture the southern colonies. Green left de Steuben in Virginia to organize a base, forward supplies and recruits, and then follow Green. However, the British landed an army in Virginia, under Benedict Arnold, giving him the responsibility to defend Virginia with the forces at hand. Not quite the way de Steuben wanted it, he had his major command. This campaign is often cited as criticism of his actual battlefield generalship as opposed to his drill field leadership. Lockhart makes a good case that de Steuben did as well as anybody could in the circumstances and better than most, though his lack of tact in dealing with local politicians hurt his efforts. With an army of changing and occasional militia, a battalion of newly recruited continentals, hardly better trained than the militia, never totaling more than a fraction of the enemy, he prevented the British from capturing Virginia or using it to support the Southern Campaign. Notably, he fought two successful delaying actions against larger forces, saving his army and critical war stocks.

There are many controversies about the veracity of De Steuben’s credentials. Lockhart establishes the he was in fact a member of the minor nobility at birth and entitled to use von Steuben. This brought him no land or income but gave him the social status to be commissioned in the Prussian Army. Baron de Steuben certainly did not discourage people from thinking “baron” was the equivalent of a British Barony. Foreign officers had by this time, a poor reputation in the Continental Congress. Benjamin Franklin and Silas Dean, the American representatives in Paris, decided that de Steuben with experience and abilities beyond his status a former captain in the Prussian Army, needed to have his credentials enhanced, reporting him as owner of massive estates and a former Lieutenant General in the Prussian Army. This was apparently not his doing, though he went along with it, and quietly let on after he was accepted as a Major General in the American army that this was inflated. Also de Steuben was prone to be ambiguous inexact and expansive in personal correspondence leaving the impression of much greater position than he had.

De Stueben's personal life was a shambles, he could not manage his personal finances, popular but with no intimate friends, charming or tactless, loyal to a fault but never letting go of a grudge. His reputation is clouded by rumors of all sorts, which if true, no primary evidence survives. As a soldier brilliant, a failure at every thing else. But it was the mess of his personal life that led him to serve in the American cause, a man with badly needed talents and abilities. Truly he helped make the American Army.

A good book for readers of all levels of interest. The authors explanations of the how and why of de Steuben’s reforms is good background for any reading on 18th Century warfare. Interesting illustrations and adequate small scale maps, some large scale maps of individual battles would be nice. Strongly Recommended.

Related: The Year of the Hangman, George Washington’s Campaign Against the Iroquois

6 comments:

This looks like a splendid book, and I will want to read it.

As for Mommouth, I suspect that, besides better drilled American units -- the arrival of some French supplies and funds made a material difference to the US performance.

El jefe

Thanks for the comment.

The Congress ratified the French alliance in May of that year so I'm not sure how much aid got thru. But beggers can't be choosers it was all badly needed.

The French were giving quite a bit of aid before the alliance in terms of money and weapons.

Thinking on the Revolution, have a look at Piers Mackesy's The War for America 1775-1783 sometime. Interesting book because it's the war of the Revolution from the British perspective, mostly from the cabinet, senior command perspective. It shows how the war was really a world-wide conflict, and how the Cold war between Britain and France really affected British strategy long before the cold war got hot.

Can't recommend that work highly enough. Makes you appreciate how impossible a military victory in America was for Britain -- that all they could do was position themselves to negotiate. It's amazing they got out of the whole war as cheaply as they did, becuase they were strategically way overstretched.

El Jefe

Thanks for the suggestion, i'll keep it in mind.

I'm trying to bone up pn the Civil War abd revolution. may never get back to Europe to follow the legions, but I can follow Grant and Lee with a trip down the road.

I ejoy Revolutionary era history, especially books on Jefferson. But my reading list is way to long right now.

Jeff

Thanks for commenting.

I know what you mean, my "to be read pile" is a bookcase.

Did you catch the Fall Of Rome Post I put up at the begininnig of July?

Post a Comment